Book Review by Raymond M. Wong

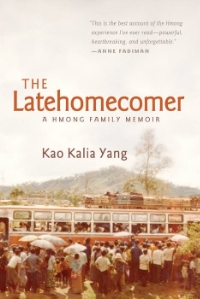

Yang, Kao Kalia. The Latehomecomer. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2008. Print.

In Kao Kalia Yang’s memoir of her family’s experience as Hmong refugees to America, the narrator wrote a high school English essay about love in response to Romeo and Juliet: “Love is the reason why my mother and father stick together in a hard life when they might each have an easier one apart; love is the reason why you choose a life with someone, and you don’t turn back although your heart cries sometimes and your children see you cry and you wish out loud that things were easier. Love is getting up each day and fighting the same fight only to sleep that night in the same bed beside the same person because long ago, when you were younger and you did not see so clearly, you had chosen them” (199).

Yang’s book is a story of separation, the loss of a country and homeland amidst the ravages of war, a people stripped of everything they held dear, and the unyielding bond of family that kept them together. Yang’s memoir is a tribute to the resilience of her family, one in which she chronicled their journey from the mountains of Xieng Khuong, Laos, to a harrowing escape from North Vietnamese soldiers across the Mekong River, to their haggard survival in a refugee camp in Thailand in which the smell of human feces overwhelmed the senses, and a passage to America by airplane to a new land, a new culture, and a new way of life.

Yang was born in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand before her family immigrated to Minnesota in 1980. She did not have firsthand experience of her family’s journey from the mountains of Laos, but she wrote about it in a way in which readers could experience it, as if undertaking that perilous trek with her family: “It was noon. The soldiers were on a truck on the dirt road—men with guns in their hands. Uncle Sai saw that they were coming, and he looked at this family of starving children; because of the fighting, because Laos had been the most heavily bombed country in the war, and because of the bombs the Hmong could not stay in place and farm, and because the Americans had left and there were no more rice drops, because they were hungry and scared and they would die if he died, he looked at them, and he looked at the truck on the road, and he ran. He ran into the Laotian jungle. He was labeled a rebel. North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao soldiers were sent to hunt him and those who would follow him” (9).

Through her memoir, Yang told the stories of her Uncle Sai, her mother and father: their childhoods; the day they met; their informal marriage ceremony in the jungle with family, a few guests, and the threat of approaching soldiers; their frantic separation while fleeing from the soldiers; their reunion and escape through the Mekong River; the family’s existence in a refugee camp; the difficulty of adjusting to another country; and a grandmother who symbolized strength, courage, and honor.

When Yang couldn’t convey her family’s story through their experience, she envisioned her parents’ first meeting: “I imagine sun-dappled jungle floors, a young man and a young woman, peeking at each other through lush vegetation, smiling shyly and then walking away slowly, lips bitten by clean, white teeth. Slow movements toward each other again, like in a dance. An orchestra of nature: leaves and wind and two shadows, a man and a woman, moving in smooth motions on even ground” (10).

Yang also wove research into her book: a covert operation by the CIA called “The Secret War” in which they recruited Hmong boys as young as ten to fight Communists in Southeast Asia, the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 and its effect on the Hmong people, and a quote from a Lao newspaper called Khaosan Pathet Lao that called for the wiping out of the Hmong.

Kao Kalia Yang wrote a memoir about her family, and in the telling of her tale, she captured the struggle and the spirit of a people unknown to many. Consider her book an act of honor and love, given to the world by a woman born to write.